Few rule changes in sports, at least in recent memory, changed the way a game is played as much as the introduction of the 3-point line changed basketball. Imagine soccer adding half a point for goals from outside the box, or the NFL adding squares in the end zone where a touchdown is nine points instead of six.

It would change the strategy, personnel, and aesthetics of both sports if these rules were added. And think about how ridiculous those rule changes sound. Well, some people who enjoyed basketball before the introduction of the 3-point line probably felt that way, too.

Today, the three-point line is a major force in basketball. And in both the WNBA and the NBA, it drives how teams scheme and the skills required to play the game. So here we take a look at the history of 3 pointer basketball in the WNBA, successful early adopters, how it’s impacted modern guards and modern teams, as well as what the future could have in store.

After single-game trials in college games dating back to 1945, and a 3-point line in the American Basketball League (1961-62), the 3-point line officially started when the American Basketball Association began its league with one in 1967-68.

“We called it the home run, because the 3-pointer was exactly that,” ABA commissioner George Mikan said in Loose Balls: The Short, Wild Life of the American Basketball Association. “It brought fans out of their seats.”

The ABA competed with the NBA, which eventually absorbed the ABA in 1976 but failed to introduce the 3-point line until 1979. The NCAA adopted the 3-point line in both men’s and women’s basketball in 1986-87.

The WNBA started with a 3-point line in its inaugural season and moved it back to its current distance in 2013. Today, the top of the arc of the 3-point line in the WNBA is 22 feet, 1.75 inches. The distance from the corners is 22-feet.

“We didn’t gravitate to the three at first,” Larry Bird told The New Yorker. “We weren’t like, ‘Oh boy, here it is!‘ No, it takes time. When they first put it in, some team took five three-pointers a game and that was a lot.”

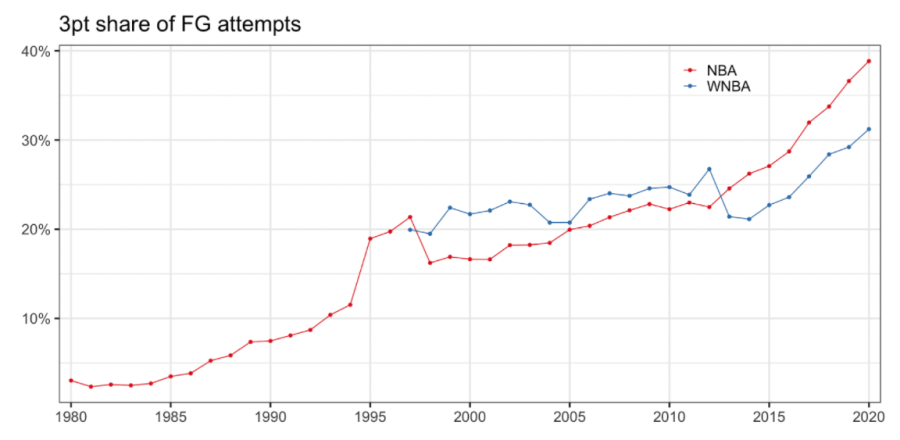

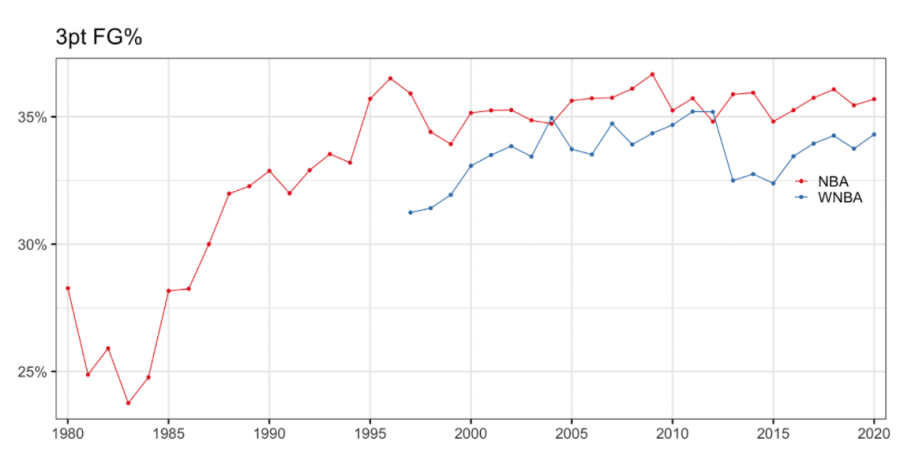

Both leagues take far more than five attempts per game today, as you can see from the chart. And you can also see how players have improved over time.

Though there was a dip in 2013 due to WNBA moving the 3-point line back.

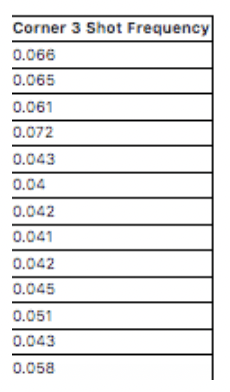

Here is a look at corner 3-point shot frequency from 2009 (top) to 2021 (bottom), per PBPStats.

It’s clear that both the NBA and WNBA are increasing the volume of their 3-point shots. In 2019, the WNBA average was 33.8 percent; in 2020 it was 34.4 percent; and so far in 2021 it is 34.3 percent. So there’s a slight increase over the past three seasons. But overall it has been between 32 and 34 percent since 2013.

Katie Smith was one of the WNBA’s first proficient 3-point shooters at a high volume of attempts. She entered the league in 1999 and shot 8.4 threes per 100 possessions at 38.2 percent. She followed that by shooting 11.1 and 11.3 threes per 100 possessions in 2000 and 2001, respectively. She won the scoring title in 2001. The Hall of Famer is currently second all-time in the WNBA in 3-point attempts and is third in 3-pointers made.

Becky Hammon entered the league in 1999 as well, and shot 11 threes per 100 possessions but at a poor 28.9 percent. That was her only season of poor three-point shooting though, as after she shot nearly as many threes per 100 possessions but only under 35 percent once in the 15 remaining years of her career. Becky is fourth all-time in both 3-point shots made and 3-point shots attempted.

Katie Smith and Becky Hammon would still be among the leaders in 3-point attempts per 100 possessions in 2021.

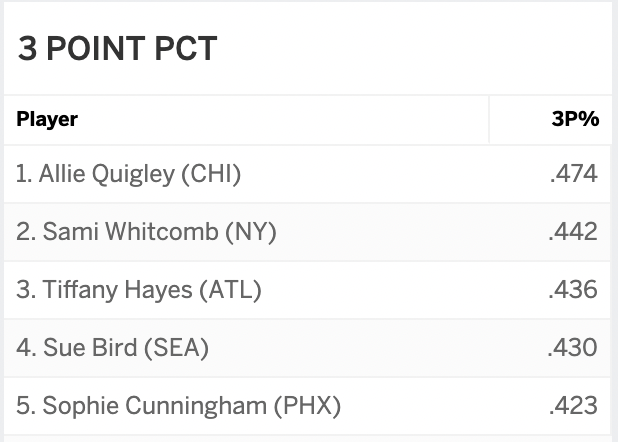

Sue Bird is still in the league and is still one of the premier 3-point shooters. Sue seems to be getting better with age, shooting 44, 46, and 43 percent in the last three seasons, adding to her phenomenal 39.3 percent career average.

After 18 full seasons – she is in her 19th – Sue Bird is second all time in 3-pointers made and third in attempts. Sue has never shot over 10 threes per 100 possessions. Her success comes from efficiency.

Notice how Sue is fantastic at shooting off the dribble. Her ability to put the ball on the floor and shoot well also helps her in the midrange. Sometimes, defenders are aggressive and run her off the 3-point line, but she can pump fake and get them in the air or dribble by them and shoot a midrange, where she shoots 37 percent from deep midrange and 52 percent from 10 to 16 feet from 2018 to 2021.

Lauren Jackson is another notable player in the WNBA. She was one of the first centers to shoot a high volume of 3-point shots. Her career average 6.8 3-point attempts per 100 possessions was ahead of her time and would still be high for centers today.

Lauren was the early embodiment of a “stretch-5,” a center who can shoot and is willing to stand outside the 3-point line. This stretches a defense and can open the lane for guards and forwards to drive to the basket.

Like Sue Bird, Diana Taurasi is both an early adopter and still one of the best shooters in the league. Diana averages 11.4 3-point attempts per 100 possessions in her career, barely below her 12 2-point attempts per 100 possessions.

But her 2-point attempts per 100 possessions have dropped below 10 since 2017, so she is shooting far more threes than twos at this point in her career. Yet her free throw attempts per 100 possessions have stayed relatively the same, just shy of a career high so far in 2021. She has shot more free throws than two point shots in 2021.

Diana is the epitome of the modern game. On offense, she hunts for the three most efficient shots in the game: layups, free throws, and three pointers.

In 2018, Diana Taurasi’s last full regular season, she drew a foul on 3.7 percent of her 3-point attempts, per PBPStats. That’s pretty good, but she drew a foul on 45.67 percent of her two-point attempts. That season, Diana was fourth in the league in free-throw attempts but only ninth in the league in field goal attempts.

How does she do this? By being such a potent shooter, Diana forces perimeter defenders to play close to her. By playing close to her, she can use her quickness to pass the perimeter defender and force another defender to rotate, or the perimeter defender chases her from behind, which is a difficult guarding position that can lead to fouls. Diana has the quickness to exploit this aggressive defending.

This play is an example of how her shooting forces the defender to play close, so she uses her quickness to get around her defender and the help defender fouls her.

Here is another foul in a pick-and-roll. Diana’s defender goes over the top of the screen to prevent an open 3-point shot. The screener’s defender stays near the paint but not low enough and Diana recognizes this. She drives to the basket and gets the defender on her hip. Diana knows the defender is out of position and initiates contact to draw the foul. A savvy play from the veteran.

So those two plays show the combination of her shooting ability and her quickness. And those two skills work in tandem. By drawing her defender close, Diana doesn’t have to be as quick as other guards to get around defenders. Her ability to shoot essentially adds a step to her quickness. That helps as Diana ages and she slowly loses some quickness. As long as she can still shoot, defenders can’t give her space.

Her most important skill is intelligence and body control. She knows when to drive and how to keep defenders in vulnerable positions. Take the second clip, where she puts her body into the defender during the shot. She knows where the defender is and how to initiate contact.

Part of what makes Diana a phenomenal 3-point shooter is her quick release. The fastest NBA shooters have a shot time of just above .40 seconds. The NBA average is .54 seconds, so we’d imagine there is a similar difference between the fastest WNBA release times and the average. The point is that 0.1 seconds makes a significant difference.

Diana doesn’t need as much space from defenders to shoot as her colleagues, so she doesn’t have to be selective or work as hard to create space. Her quick release also allows her to be devastating off the dribble because defenders have less time to react and contest a shot. Diana is also six feet tall. The average height for a guard in the WNBA is 5-foot-8 inches. Her height gives her a high release point and that makes it difficult for defenders to contest the shot.

Diana’s range is also what makes her special. She is shooting from spots defenders don’t think about guarding. What is most impressive is her ability to maintain a quick shot even while deep behind the 3-point line. Part of this comes from Diana’s consistent leg bend. Diana barely bends her legs for the power she needs to shoot from long range. Instead, her power comes from her arm and wrist. Her consistent leg bend provides the same power and motion no matter how far she is from the 3-point line. This makes for a more accurate and consistent shot.

Three point shooters also provide opportunities for other players because of their threat to shoot. This is often called gravity. Watch the play below: Diana and Brittney Griner start a dribble-handoff. The Seattle Storm defenders jump to Diana to prevent the 3-point shot.

Diana passes the ball to her teammate near the corner because her defender is dropped into the paint, but she then steps to the ball handler. Brittney recognizes this and she has an easy roll to the basket because of the open lane, and her defender is focused on Diana. So she rolls, gets the pass, and scores the easy basket, all because of Diana’s shooting threat and the defense’s reaction to it. Diana will not get any traditional box score credit for this either. She does not get the assist nor the points.

All in all, Diana is a deadly combination of 3-point skills.

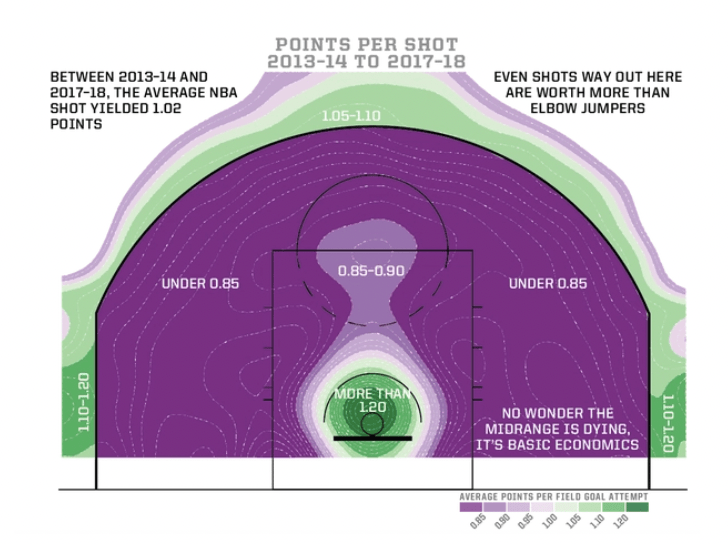

The midrange is dead, as some pundits or fans will say. Are they right? Well, sort of, but most importantly, it depends. The preference for 3-point shots over midrange shots is simple logic. Why take a deep two when a player could move back a few feet and shoot a three at a similar percentage?

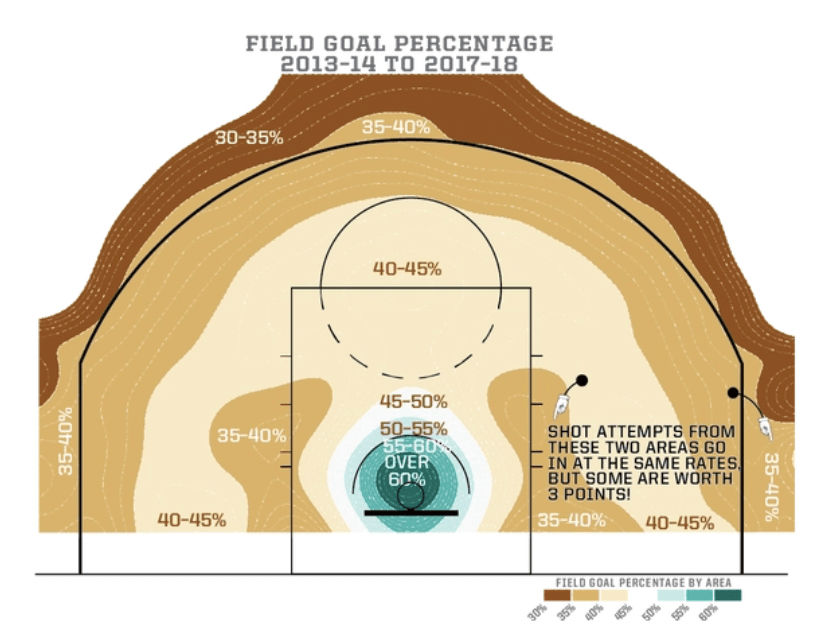

Kirk Goldsberry, in his book SprawlBall: A Visual Tour of the New Era of the NBA, uses two charts to show why the midrange shot has moved beyond the 3-point arc.

The numbers are roughly similar for the WNBA. This season, the WNBA’s above the break 3-point average is 31.2 percent, according to PBPStats. The corner-3 average is 35.95 percent. The league average for a short midrange shot is 38.6 percent. It is 37.01 percent for a long midrange. That’s a value of .74 points per shot from long midrange compared to .93 points per shot from above the break 3-pointers. The corner-3 is an exceptional 1.07 points per shot so far this season. Math!

But basketball is more complicated than that. All of this data needs to be tailored to teams and individuals. Players who shoot closer to 45 to 50 percent from midrange raise the value of the shot. For example, Indiana Fever guard Kelsey Mitchell has attempted the fourth most midranges this season, according to the WNBA website, and she’s making them 47.1 percent of the time. That’s .94 points per midrange shot, right around league average for an above the break three. Kelsey is shooting 30 percent from 3, putting her at .90 points per 3-point shot, so her midrange has been more efficient in 2021 than her threes. Kelsey is more the exception than the rule. But as always, shot selection should depend on many variables like who is shooting.

Defense is the other important variable. If a team decides it doesn’t want to allow any open 3s, then they might sacrifice open midrange shots. Many defenses are happy to allow it. And if the midrange is open, then teams will most likely convert a higher percentage of them than average and it will be a more efficient shot. If a defense leaves Kelsey to take open midranges then she might start to hit more than half of them. If a defense schemes to take away Kelsey’s midrange, that could create open threes or layups for teammates.

The drop-coverage defense is a common way to force teams into midrange shots. If the offense initiates a pick-and-roll with a guard and a center, then the opposing center will stay “dropped” in the paint to protect the basket. The opposing guard will fight over the screener and run the ball handler off the 3-point line to take away an open three. This defensive coverage leaves the long midrange open.

So no, the midrange is not dead, but as always it depends on who takes the shots and what shots the defense allows. But, it’s clear that a contested three is always better than a contested long midrange, and so on and so forth.

The introduction of the 3-point shot changed the dimensions of basketball. The basket is 10 feet above the ground so it remains a vertical game. But the 3-point shot added a horizontal dimension.

Before the 3-point shot, the best shots were the ones closest to the basket. Centers dominated basketball, and guards were judged on how well they passed the ball to centers. Now, the 3-point shot makes shot selection a more complex process.

Most offenses work to get shots close to the basket and behind the 3-point line. So the defense is stretched to defend both. Centers have to be more mobile on defense. Guards also have to be better at fighting through screens and contesting 3-point shots without fouling.

Take this play by Chicago Sky center Candace Parker. She has to defend the rim and the corner-3 in one possession. It’s an incredible feat of athleticism, and lesser defenders wouldn’t be able to. But it’s an example of how the 3-point line forces defenders into difficult situations.

Traditional centers would’ve been seen as defenders because of their height and ability to block shots at the rim. But now, as Candace shows, many centers need to be able to move to the perimeter.

The 2019 Washington Mystics are one of the greatest offensive teams in history. They had the highest raw and relative offensive rating in the league since 2009; they shot the most threes in a season in history; they had the second highest eFG% since 2009. Elena Delle Donne is the only player in league history with a 50-40-90 season. Their list of accomplishments goes on and on. Oh, we should also mention they won the 2019 WNBA title.

“I hope people don’t catch up to us yet. I hope we stay ahead of the curve for a while,” Washington coach and general manager Mike Thibault told the Wall Street Journal that season.

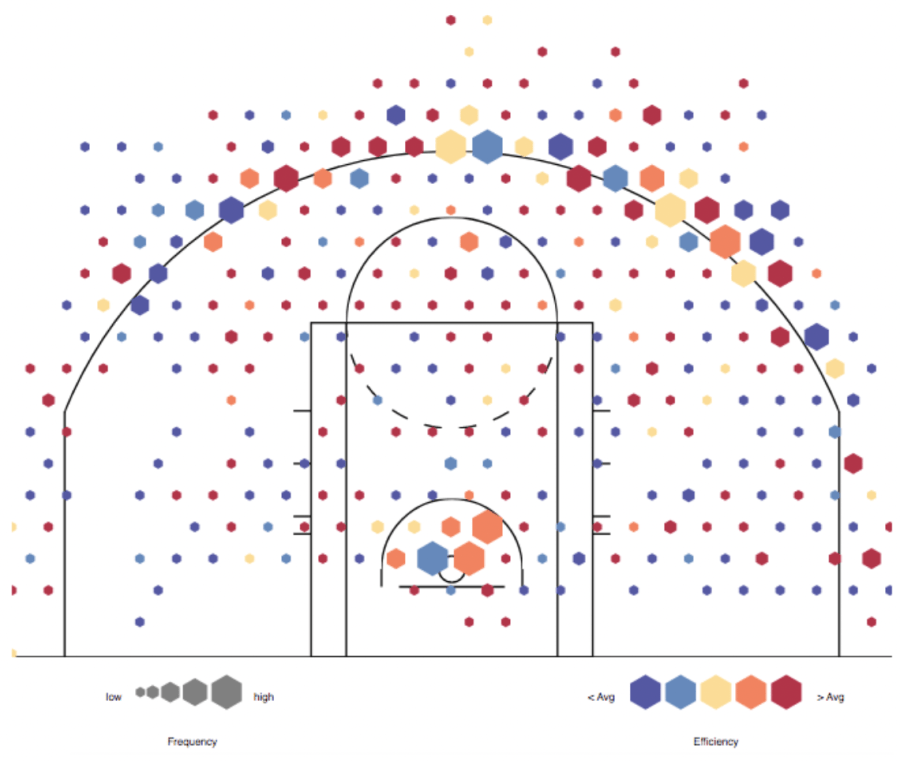

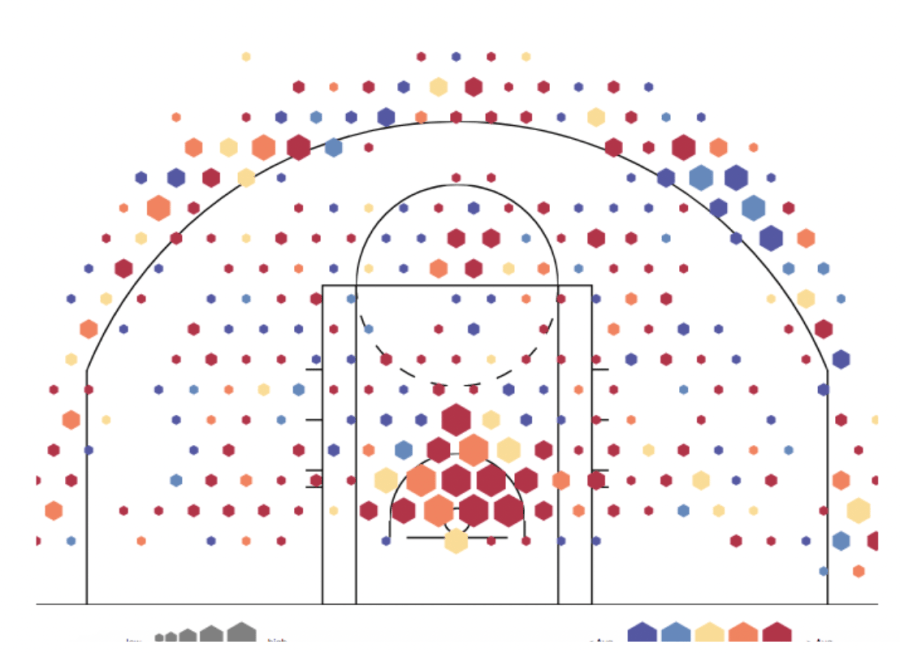

Here is their shot chart:

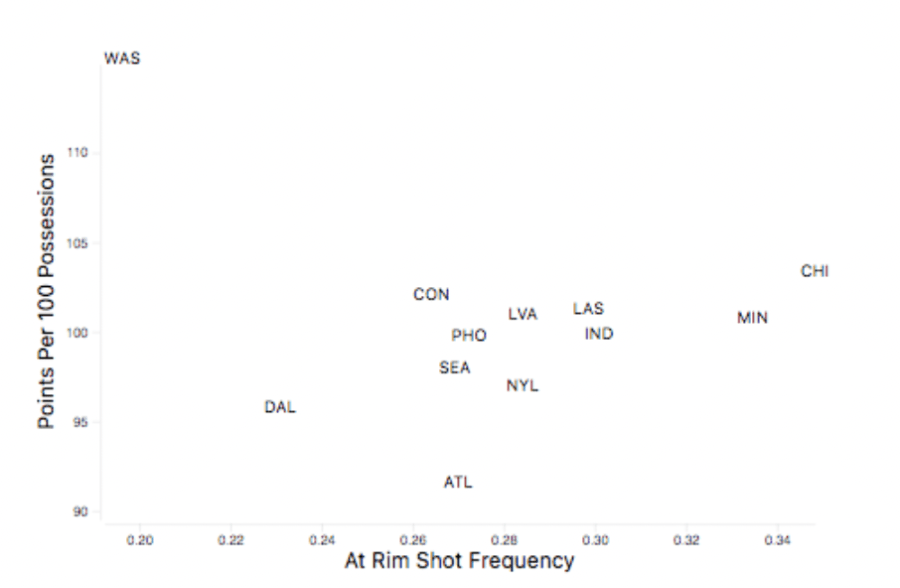

By now you notice how their volume of shots is concentrated behind the 3-point line and at the rim. But their frequency of shots at the rim was significantly below the rest of the league.

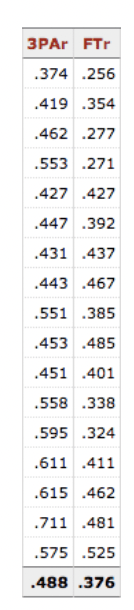

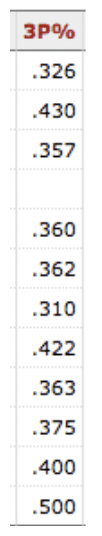

They were efficient at the rim, but they were a team full of long range snipers. Below is their individual 3-point shooting percentages, per basketballrefernce.com. They were not relying on a few players to shoot a high volume and a high percentage, they relied on all but one of their players to shoot well.

The 3-point shot has changed more than just halfcourt offense and defense. The 3-point shot is also a weapon in transition. Before the 3-point line, the goal for an attacking team in transition was to get a layup. The defense’s goal is to stop a layup. In today’s game, the goal, like in halfcourt offenses, is to get a layup, an open 3-point shot or free throws.

Given that most offenses have an extra player in transition, the defense is forced to make a decision: give a layup or give an open three.

For example, here Seattle has the ball in transition and it is a 3-on-3. But Brittney Griner does a poor job of locating Jordin Canada in transition and loses her, creating a 3-on-2 for Seattle. Sami Whitcomb shot 36 percent from three that season and she is to Canada’s right. She runs to the 3-point line in transition to create space and force her defender to choose between stopping her or Canada. The defender chooses to stay with Sami and Jordin gets an open layup.

It’s an example of how proficient 3-point shooters can impact transition basketball. The defender should stop Jordin and the ball, because Jordin makes that at least 90 percent of the time compared to Sami’s 36 percent from three that season (math!), but she stays with Sami.

It’s an understandable decision from the defender because players are instructed to stay as close to shooters as possible throughout the game. So it’s difficult to recognize the threat and adjust in the moment. Defenses work hard all game to stop the second best shot in the game: the open 3-pointer. The bind that a transition 3-point threat creates? It can make way for the best shot in basketball: the open layup.

The most obvious question for the future: How many 3-pointers are enough? What’s the Goldilocks zone for 3-pointers? Not too many, not too little. Will players get more efficient, or have we reached maximum efficiency for the human body?

Like with free throws, we understand that the best humans, given a large enough sample size, top out around low-90 percent. Of course, not all threes are the same like all free throws are, but the same general logic applies.

If players are shooting from deeper and deeper, could we see a four-point line? Not anytime soon. Neither the NBA nor the WNBA have had any serious discussions about adding one. But it’s a fun exercise to think about. The Harlem Globetrotters use it. The BIG3 basketball league uses a 4-point spot.

But, some coaches do use it in practice. Former Atlanta Hawks coach Lloyd Pierce had his organization paint a 4-point line on the court to teach his team and young guard Trae Young, who shoots from 30 plus feet often, about proper spacing. He wants Trae to initiate plays from that distance to stretch the defense. They also have a special box in the corner that is worth four points so players prioritize the corner-3. Lloyd Pierce is not the only coach to use it. He took it from former Philadelphia 76ers coach Brett Brown.

“Lloyd not only wants Young to shoot from the 4-point line but to make plays from there, too. Expanding the floor outward, in turn, creates space in the paint for big men such as second-year breakout John Collins. If a guard like Young can initiate a play from behind the 4-point line, defenses are forced to cover more ground and, eventually, make difficult choices and compromises,” ESPN’s Malika Andrews wrote.

Northwestern Sports Analytics Group wrote a small piece on the hypothetical 4-point line. In it they showed how the frequency of 30+ foot shots and field-goal percentage of those shots are both increasing in the NBA.

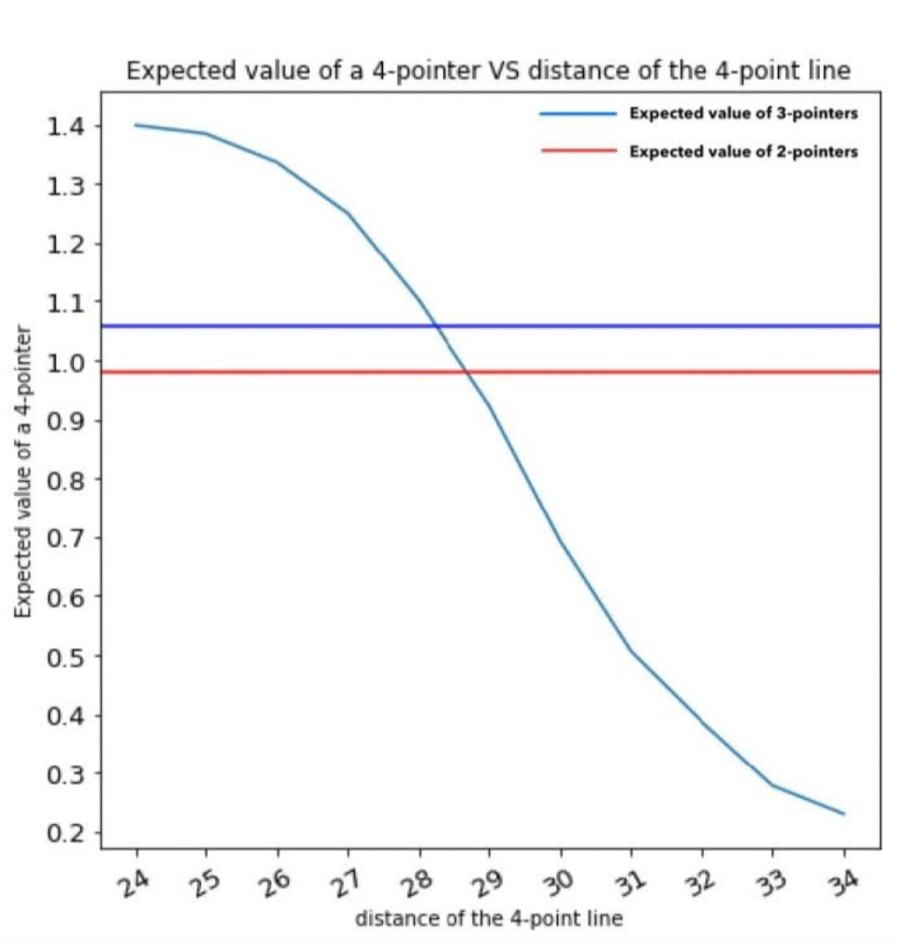

Given how the WNBA has paralleled the NBA in its frequency and efficiency, it’s conceivable to think that could continue if the WNBA introduced a 27-foot four-point line. Here, NSAG showed the expected value of a 4-point shot for a 4-point line at various distances. Here is the graph.

If the four point shot is ever introduced, then we’re sure some pundits will be on television saying it ruined the game.

Up next, learn more about the evolution of the center position in the WNBA.