On March 3rd, 2021, two-time WNBA MVP and center Candace Parker appeared on TNT’s “Inside the NBA.” She was an analyst with two-time NBA MVP and center Shaquille O’Neal and eight-time All-NBA guard Dwyane Wade when they discussed the tactical challenges facing modern defenses.

Candace Parker: “The NBA switches now, right?”

Shaquille O’Neal: “Why?”

Candace Parker: “Because everybody can shoot threes.”

Shaquille O’Neal: “What happened to man up?”

Candace Parker: “Because you’re going to be manning up trying to recover back to your man, and they’re going to hit a three just like [Nikola] Jokic did.”

Shaquille O’Neal: “What ever happened to pre-rotating?”

Candace Parker: “Then they move the ball around.”

Dwyane Wade: “You have four to five three-point shooters on the court you ain’t going to rotate in enough time.”

The full conversation is here — an interesting discussion about the way basketball is played today. The crew can discuss pre-rotating, switching, dropping or any other kind of defensive coverage, but it is all preceded by Candace’s main point: “Because everybody can shoot threes.”

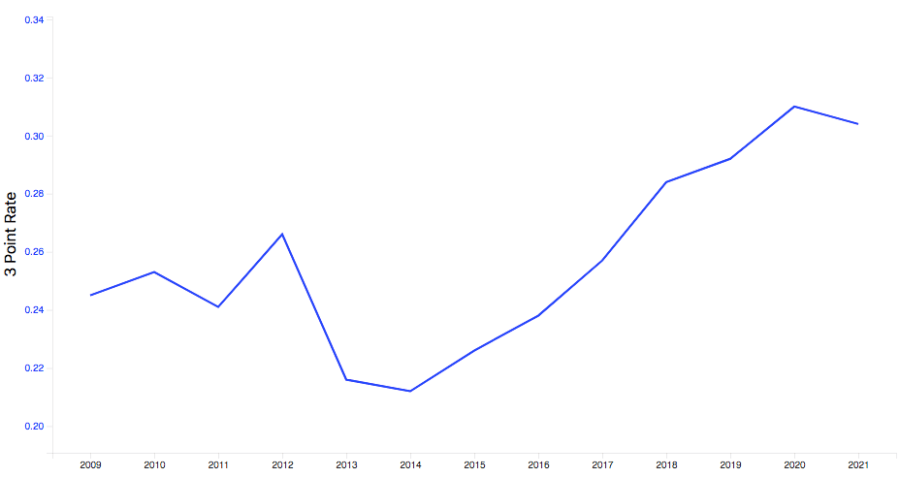

When the NCAA adopted the 3-point line in women’s basketball in 1987, it began a gradual evolution of the game and the skills required to play each position. The center, the tallest player who spends the most time by the basket, was the subject of the most intense natural selection. The 3-point line forced centers further away from the basket as the game became trended toward the perimeter. The traditional post-up, where an offensive player stands with her back close to the basket, is no longer the primary offensive action. Actions with the threat of a 3-point shot are more common than they used to be. In the WNBA’s inaugural season in 1997, the defunct Houston Comets shot a league-leading 23.4 threes per 100 possessions. That would’ve been 10th in 2019.

The way basketball is played changed as 3-point rate increased. So what does the game require from a modern center? How has that changed over time? And who are the centers today who have those skills? Today, we’re going to reveal all the answers.

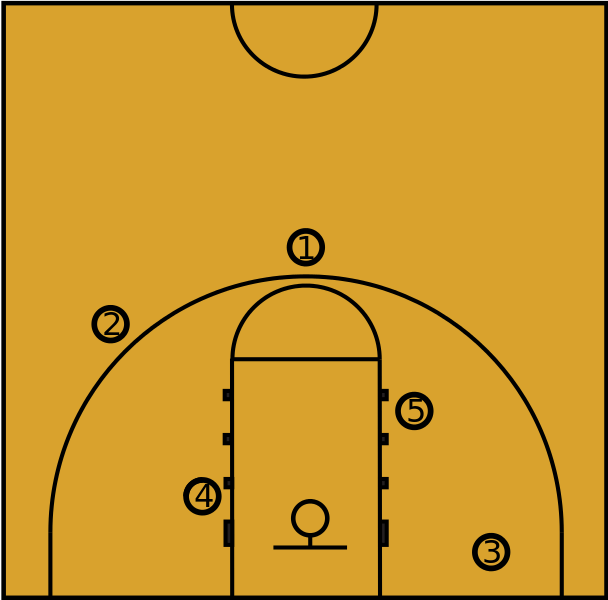

The center position is typically the tallest position in basketball. The average height of centers in the WNBA is 6 feet 5 inches. Because of their height, centers are expected to block shots at the rim and rebound missed field goals. On offense, centers often set screens for guards or post-up their defender near the basket. They are not expected to dribble. The position is commonly referred to as the “five” and is part of the “front court.”

To understand the rapid change in how the center position is played in the WNBA, it’s important to analyze how it was played in the late 1990’s and early 2000’s. At the time, it was more common for the center to play closer to the basket. And while centers were asked to set screens in pick-and-rolls, few were asked to pick-and-pop, where the screener stays at the perimeter to be a threat to shoot instead of rolling to the basket. This changes how an offense functions and it changes how a defense covers the play.

Take this play from the 2001 Western Conference Finals between the Los Angeles Sparks and the Sacramento Monarchs. A Monarchs’ guard begins a pick-and-pop with Sparks center Lisa Leslie as one of the defenders. The screener pops, but she is not a threat to shoot. Lisa drops to cover the rim and Lisa blocks the shot. Had the opposing power forward been a small threat to shoot, Lisa might’ve stayed with her, allowing an open lane to the basket.

Lisa’s ability to block this shot is still impressive and a testament to her athleticism, but her decision to drop to the rim was easy. Without any threat to shoot a three on a pick-and-pop, the screener can be removed from the play, and now the Sparks are playing 5-on-4 defense.

As the three point attempt rate increases, players spend more time beyond the 3-point line, which increases spacing. In 1999, the four All-Star centers averaged 1.1 3-point attempts per 100 possessions that season. In 2019, the five All-Star centers averaged 2.2 attempts per 100 possessions.

Below is a screenshot of a possession in game two of the 1999 Finals between the Houston Comets and the New York Liberty. The possession begins with four Liberty players inside the arc. One player comes to help point guard Becky Hammond, but the others stay inside the arc until Becky breaks into the lane and the play ends with a midrange basket. There is no threat of a three on this possession. It is hard to see a modern offense having zero 3-point threat. Also, look at the lanes in which Becky could drive to the basket. There are none. Four offensive players inside the arc means there are four defenders in the arc to block the driving lanes. Pause at the start of possessions today and you will rarely see four players inside the arc.

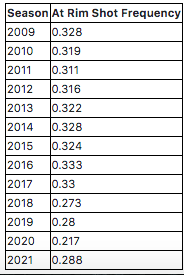

Getting shots near the basket is still a priority for all offenses. Traditional post-up may be less common, but a shot near the rim is still the best shot in basketball. PBP Stats also shows how frequency of shots at the rim have stayed relatively the same from 2009 (when they started tracking the data) to 2017.

Lauren Jackson, the Australian international, entered the WNBA in 2001 and became the first center to show the future of basketball. Her ability, at 6 feet 6 inches tall, to post-up, shoot from the perimeter and dribble was ahead of her time as a center. The 7-time WNBA First-Team center still ranks 10th in career 3-point attempts.

“The things she was doing, at her size, you never saw anybody else do,” Sue Bird told FIBA. Her 47-point game highlights are here.

Lauren earned one of her three MVP awards in 2007 when she had a 56.8 effective field goal percentage, impressive for a center shooting 6.2 threes per 100 possessions. Lauren Jackson was also well respected on defense. WNBA coaches voted her Defensive Player of the Year in 2007 and she was one of the premier rim defenders in the league.

Her play style was cutting edge and what followed were many centers mimicking her skill set: Candace Parker, Elena Delle Donne, Brianna Stewart, and others.

One of the WNBA’s all-time greats. Yolanda Griffith was the 1999 MVP and 5-time All-WNBA center. She was also a Defensive Player of the Year and member of a WNBA All-Decade team.

Margo Dydek was the tallest WNBA player ever at 7 feet 2 inches. She is the WNBA’s career block leader and had seven seasons with over six blocks per 100 possessions.

So by now you know that perimeter shooting changed the game. Modern basketball is defined by spacing. That much is clear. So let’s jump into something a little hazy. The center position is more blended than ever. As basketball becomes more spread out, the lines between a power forward and a center blur. Basketball Reference and the WNBA’s website will list players as “center-forward.”

Some teams will play “small-ball,” where a smaller, more nimble player will play center. In prior decades, this player would have been considered a power forward. Power forwards are traditionally smaller, more mobile on defense and better shooters. The sacrifice of playing a smaller “center” could be rim protection, but the players who flex between the center and the power forward position are often good rim protectors for their size.

Enter Breanna Stewart.

She is one of the best players in the league, but her status as a center is debatable. She’s listed as a forward and she mostly plays with a center in 2021 (Mercedes Russell). But in the 2020 season, Breanna was the tallest player in the Seattle Storm’s most used and effective lineup. In both the regular season and the playoffs, a lineup of Sue Bird, Alysha Clark, Natasha Howard, Jewell Loyd, and Breanna Stewart was +85 in 258 minutes. They shot 43.5 percent from three on route to 58 effective field goal percentage and a WNBA title. That lineup had a fantastic defensive rating as well, allowing only 88 points per 100 possessions. Small sample, sure, but the numbers from 2018 are similar.

Here Breanna Stewart comes off a screen and hits a contested shot.

She can still post-up.

And she can hit threes.

Regardless of whether she plays at a center or not, her shooting ability puts opposing centers in difficult defensive actions. Modern centers must account for more than just defending the rim, as many offenses look to take advantage of a center sagging off perimeter players.

Take these two plays from Seattle that involve Breanna as a power forward and either Mercedes Russell or Ezi Magbegor at center.

Breanna sets a screen for Sue, but she slips the screen to the 3-point line. That’s when the center sets a screen on Breanna’s defender, who is occupied with Sue for long enough so she can’t fight through the screen in time. The opposing center is dropped into the paint, so she can’t cover Stewart at the 3-point line and Stewart has an open shot.

So Breanna is playing the power forward position, but the offensive action targets the center. Because the center is naturally dropped into the paint, she would have to be very mobile, or proactive, to reach Breanna in time. These are the demands of a modern center on defense because the game revolves around spacing and more offensive players able to shoot threes.

“I don’t know if the game has seen anyone that is 6-4 and can take the ball from one end of the court to the other and run past most guards. Can block your shot. Can score in the post and shoot a 3 and be comfortable making 4 of 5. Not to mention she is a great passer,” Breanna Stewart’s college coach, Geno Auriemma, said.

The traditional center is not dead. Being taller and bigger than most players on the floor is still an advantage. Liz Cambage is 6 feet 8 inches tall. Because of her size, she can do this:

She scored a layup on this play. Spacing in basketball is more important than ever, but as long as the basket is 10 feet high, verticality will play an important role. Centers can still take advantage of their size when smaller players switch onto them. Basketball is simple sometimes.

Shot blocking is a classic measure of defensive verticality. As referenced before, the best shot in basketball remains a shot near the basket, so defenses still scheme to guard it. A shot-blocking center is often crucial to doing so. The goal of a defense is to prevent the ball from going in the basket. There is no better way of doing so than stopping the opposing team from shooting, and the best way to do that is either force a turnover or block the shot.

Brittney Griner is the WNBA’s best shot blocker. She has the three highest block totals in a season since 2009.

Take this play against the Las Vegas Aces in 2018. Las Vegas runs a pick-and-roll at the 3-point line and Brittney rises to the level of the screen. Phoenix Mercury guard Briann January goes over the top of the screen to run Aces’ guard Kelsey Plum (a 43 percent 3-point shooter that season) off the 3-point line. So Kelsey, realizing she just has Brittney in front of her, drives to the basket. Against most centers, Kelsey gets a layup.

Her acceleration is too much to handle, so any kind of contest or shot blocking at the rim is neutralized because the pick-and-roll dragged the center out to the perimeter. But Brittney has the athleticism and the wingspan to recover. She flips her hips toward the basket so she can run parallel with Kelsey. This gives her the acceleration necessary to jump. Her 7 foot 4 inch wingspan does the rest.

Another important aspect of defense is help defense and rotation. Few centers are better in this department than Candace Parker. She is another forward-center hybrid. During her time at the University of Tennessee she was listed as a guard, forward, and a center, and like Breanna Stewart, that is an accurate summation of her skills.

Basketball Wiki describes help defense as: “Help Side is one of the primary aspects of Team Man to Man Defense. It’s the application and rotation of weak side defenders helping out the players on the strong side who are defending the ball.”

Below is an example of Candace’s abilities as a help defender from 2020. In this play, the Washington Mystics are running a pick-and-roll on the right side, and Candace comes across to cut off the lane to the basket. The Mystics counter the help defense by swinging the ball quickly to the weak side. Candace is on the right side of the key when the Mystics begin passing the ball. By the time the ball arrives to the player in the left corner, Candace closes the shooter and blocks the ball.

It is an impressive feat of athleticism that few, if any, can play with. Because offenses are filled with 3-point shooters, helping on defense requires more speed and intelligence. As offense stretches the space, defenses must recover faster, and having a center as athletic and intelligent as Candace is an ace up the sleeve of defenses. It is a big reason why coaches voted her Defensive Player of the Year in 2020.

Candace is also a phenomenal dribbler and passer, which makes her deadly in transition.

Most centers would grab the rebound, pause, and look for a guard to pass it to. Candace doesn’t do that. She rebounds the ball and initiates a fast break. It’s a four on two because of her speed and dribbling ability. She’s dribbled to half court when a Washington Mystics’ defender stops and forces her to pass the ball. What does Candace do?

She rifles a no-look pass to Courtney Vandersloot down the left side, who makes one more pass to Kahleah Copper who scores. Candace has only played six games so far this season, but she is averaging 7.3 assists per game. The fabulous transition pass was not one of them. In this play, Candace will not get credited with an assist. Courtney will, and Kahleah will get two points.

What does Candace get? On a traditional stat sheet she gets a rebound, but that’s it. Assists are a measure of passing not creation. Candace created this basket with her ability to dribble and pass, and those skills, especially dribbling or the ability to drive by someone, don’t always show on a stat sheet.

Well, that’s complicated. Team rebounding is important, but individual rebounding statistics don’t always show who is good at it. Centers often rank toward the top of total rebounding lists. Initial positioning means a lot to someone’s chances of grabbing a rebound. For most of basketball history, centers were the tallest players and closest to the basket, so they were most likely to grab a rebound. It is hard to distinguish what is actual skill versus the nature of the position.

Rebounds are broken into two categories: offensive or defensive rebounds. Many defensive rebounds are grabbed without any contest by an opposing player. In other words, any regular, replacement level player would have grabbed that rebound. Again, it’s very difficult to assess rebounding as a stat versus rebounding as a skill.

Centers that are better at guarding perimeter players might also lack defensive rebounds because they’ve switched onto a guard and they are now out of prime rebounding position. The ability to switch onto a guard is a valuable skill for a center, so if rebounds are a way you judge a center, you could inadvertently filter out a valuable skill.

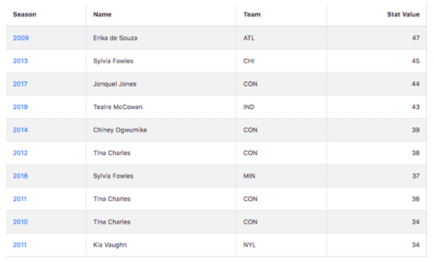

Offensive rebounding value is easier to observe in real time. Defenders should have better positions for rebounds because they should be closer to the basket than offensive players. An offensive rebound can also lead directly to a putback. Below is a chart for the ten most putbacks in a regular season since 2009, per PBP Stats. Tina Charles and Sylvia Fowles have multiple seasons in the top-10, so while it’s difficult to judge individual rebounding skills from stats, it’s easy to see those two provide more than most on the offensive glass.

We’ll leave you with a deep dive into the issue.

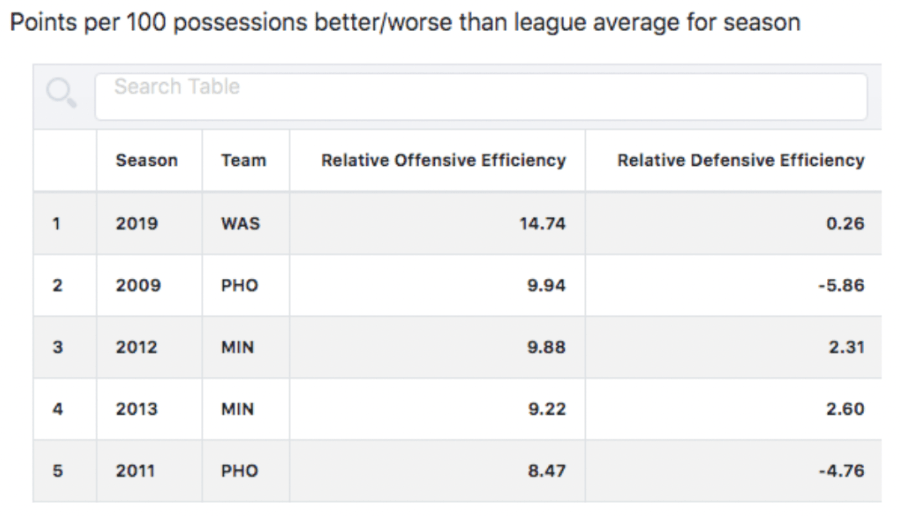

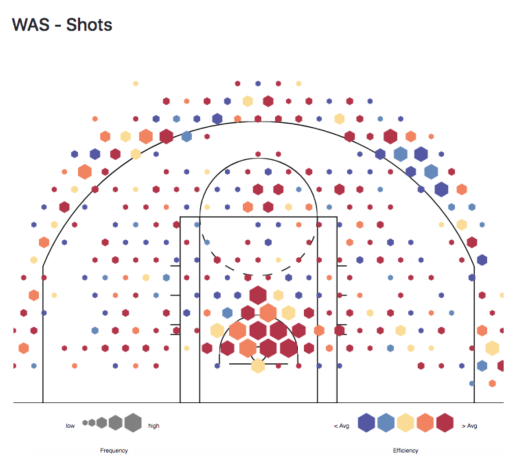

The Washington Mystic’s 4/5-out offense is one that requires a center who can shoot. The 5-out (or 4-out) offense simply means five or four players start outside the 3-point line, and in 2019 the Mystics perfected it, winning the title while having the greatest relative offensive rating in league history, per PBP Stats.

The Mystics had an offensive rating of 112.9 points per 100 possessions, and they had by far the highest 3-point rate in the league that season.

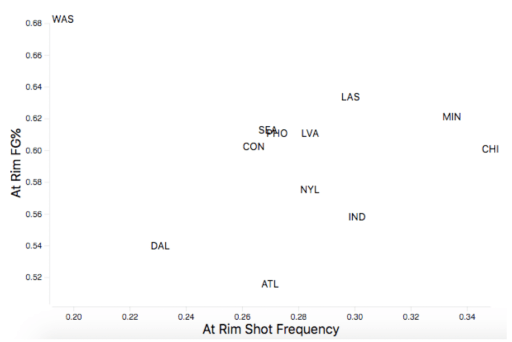

They did sacrifice shots at the rim. But they had the highest at-rim field goal percentage in the league that season, partially made possible by the spacing created from multiple potent 3-point shooters. The Mystic’s played the Connecticut Sun in the 2019 Finals, and the spacing dragged Sun’s center Jonquel Jones away from the rim. Jonquel had the second-highest blocks per 100 possessions in the league in 2019.

Elena Delle Donne was a big reason for that. The Mystics’ center shot seven threes per 100 possessions that season and made 43 percent of them.

Below is the shot chart for the 2019 Mystics. It is all three point shots or shots at the rim.

Elena hasn’t played since, but the Mystics added Tina Charles for the 2021 season and she has filled the role of a center who can shoot threes. In her first five seasons, Tina barely shot threes. She increased her 3-point rate starting in 2017, and this season she’s exploded to 8.6 3-point attempts per 100 possessions.

Tina’s quick increase in 3-point attempts is a snapshot of how basketball changed for centers, and how quickly they had to adapt.

The question about the future of basketball remains about 3-point shot frequency. Will it continue to increase? Can players continue to get better at shooting a high percentage and a high volume? Will more teams have shot charts like the 2019 Mystics? The same questions apply to the center position. The center position is not “dying,” as some have written.

We believe the power forward position and center position are combining. The hybridization of the position will become more valuable as shooting and defensive mobility do. That does not mean centers with traditional size or lack of mobility will disappear. They will become players who are deployed based on matchups and schemes. Breanna Stewart and Candace Parker-like players won’t necessarily become more common, but they will become more valuable. Breanna and Candace are one of a kind, but they are part of the shift in categorizing centers. The word center might disappear, morphing into “forward” or “big.”

Maybe in the future some WNBA player will be on “Inside the NBA” telling Candace why and how the game has changed since she played.

Up next, learn more about center Liz Cambage.

Don’t let WNBA stories go untold. Would you be willing to send a $5 tip to our Venmo tip jar because it helps support our reporting? @megsterr.

Or our Paypal: